Thanks to the Super Bowl, the N.F.L. is often discussed in terms of a before and an after.

The era before the 1966 season, when the N.F.L. and A.F.L. created a championship game between the leagues that became the greatest spectacle in American sports, was defined by strong defenses, running games and a group of star quarterbacks — Sammy Baugh, Otto Graham, Y.A. Tittle — who are discussed in the vaguest, yet grandest, of terms. Each was a Paul Bunyan-like hero who dealt with impossible weather and poor equipment, yet accomplished feats we can’t possibly understand but are meant to appreciate.

The time after the Super Bowl has its own star quarterbacks — Terry Bradshaw, Joe Montana, Tom Brady — each of whom has been scrutinized to an almost unimaginable extent.

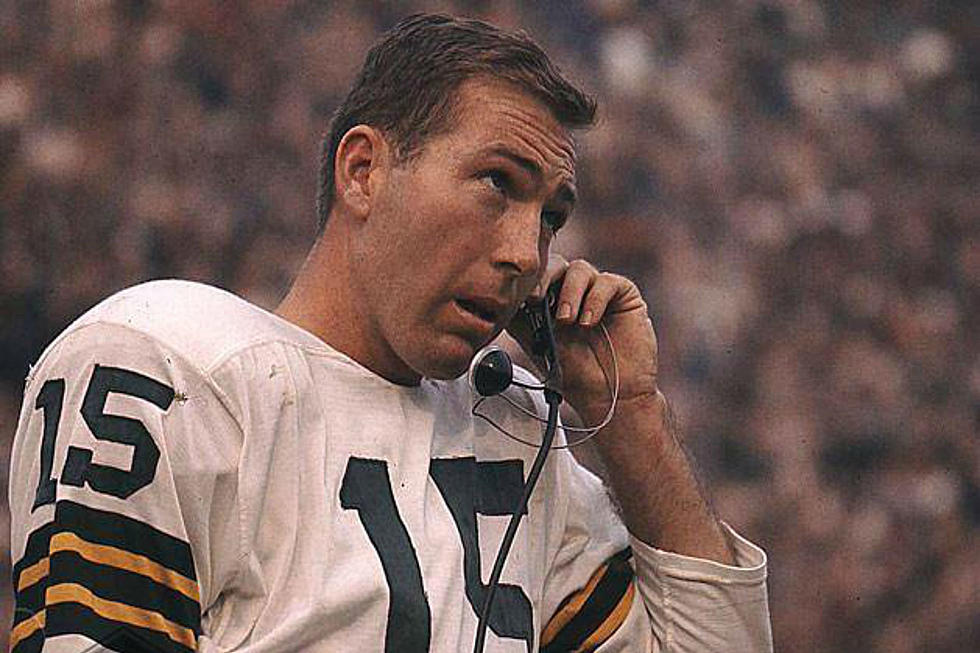

In the middle is Bart Starr, who died on Sunday at 85. He ushered in the Super Bowl era with two championships for the Green Bay Packers. The most valuable player of Super Bowl I? Starr. Super Bowl II? Starr again. Despite that, Starr manages to get lost in history. We know too much about him for a mythology to carry him through the years, yet most fans don’t know enough about him to truly appreciate how much he meant to his team.

Marc Stein’s Newsletter

Starr, like Montana and Brady, was a star synonymous with winning in a way that went far beyond simple statistics. The modern era, which he and Baltimore’s Johnny Unitas helped usher in, led the N.F.L. on a path to being America’s richest and most popular sport. And while the transition from the league’s wilder early days to its sleek and modern present would quite likely have happened without Starr, he and the Packers helped create the early blueprint for players of the soon-to-be-merged N.F.L. and A.F.L. to follow.

Amazingly enough, considering the amount of ink devoted to football stars over the last century, some struggle to even say how many championships Starr won. More often than not, he is referred to as a two-time Super Bowl winner, a true statement that shortchanges him three N.F.L. titles before the big game was born.

A 17th-round draft pick out of Alabama, Starr struggled to a 3-15-1 record through his first three seasons, never truly finding his fit. In 1959, the Packers were far removed from their heyday of the 1930s and 1940s. In stepped Vince Lombardi, whom the team hired away from the Giants. He and Starr went on to create one of the greatest pairings of coach and player in American sports history, surpassed by only the likes of Bill Belichick and Brady of the New England Patriots.

Over the course of nine seasons, Lombardi and Starr knew only success. A team that had gone 1-10-1 in 1958 (0-6-1 with Starr starting) would never record a losing season under Lombardi. The Packers improved to 7-5 in 1959, played for the N.F.L. championship in 1960, and won the N.F.L. title in 1961. And then they did it again in 1962.

In a time before 24-hour news cycles and the constant debate about player legacies, Starr was content to simply win games. He never reached 2,500 passing yards or even 20 touchdowns in a season, yet won five championships over a span of seven seasons. He was an All-Pro just once, but remains the N.F.L.’s career leader in postseason passer rating. To this day, he is the only quarterback of the forward pass era (after 1933) to win the N.F.L.’s title game three years in a row.

“There’s nobody who could put a team in a better position with what Vince wanted to do,” the former Packers running back Paul Hornung said of Starr in The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel in 2013. “He gave him control of the team. He gave him authority to do whatever he wanted to do. And that’s pretty strong.”

To honor Lombardi for having won the first two Super Bowls, the N.F.L. named the Super Bowl trophy after him. But when it came time to name the Super Bowl M.V.P. trophy, the league chose to honor Pete Rozelle, the former commissioner, rather than Starr, the player who won the first two.

The extent to which Starr’s accomplishments have been diminished by the “before and after” nature of N.F.L. coverage was never more apparent than after Super Bowl LI in 2017, when Brady was heralded for winning his fifth title, thus passing Montana and Bradshaw for the most by a quarterback in the Super Bowl era. When Brady won his sixth title two years later, thus passing Starr, the feat was mostly an afterthought.

For Starr’s accomplishments to be so easily reduced to asterisks seems to be a product of the tendency of sportswriters to try to split up the N.F.L.’s history into digestible segments. When discussing statistics, you will see terms like “post-merger,” meaning since the 1970 N.F.L.-A.F.L. merger, or “Super Bowl era” meaning since 1966. Positions changed, the number of games played changed, the number of teams changed. Passing became more prevalent, substitutions became more common, and free agency and the salary cap combined to create far more player movement than the league had previously seen.

So where does that leave a player like Starr who played 10 seasons before the Super Bowl was created and six in the so-called Super Bowl era?

It’s hard to call a Hall of Famer who had five championships and a Most Valuable Player Award on his shelf underrated, especially one as revered in Green Bay as Starr. But in the grand scheme of football he may be the person whose accomplishments have been most overlooked.

It may be true that there was a before and an after, and the Super Bowl may be the right place to draw the line. But Starr managed to serve as a seamless bridge between those eras. He was the unbeatable force of the N.F.L. that gave the A.F.L. something to strive for. In poetic fashion, it was in 1969, with Lombardi retired and Starr suddenly feeling the effects of age and injuries, that Joe Namath and the Jets of the A.F.L. were able to shock the football world by toppling Unitas and the Baltimore Colts of the N.F.L. in Super Bowl III.

Beyond anything else, maybe even beyond Starr’s championships, it is what happened in his absence that makes Starr a player worth bringing up any time the greats are debated.Starr’s accomplishments may not resonate quite as well in other cities, but in Green Bay he is revered by fans and players alike, with Brett Favre, right, and Aaron Rodgers (not pictured) regularly praising him.CreditMike Roemer/Associated Press